On the start of Maternal Mental Health week, we are delighted to publish this inspirational article written by Kristina Cowan from the United States. Kristina also supports our work as a member of Board of Advisers.

About the author

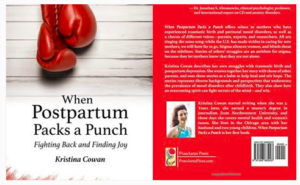

A graduate of Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill., Kristina Cowan has more than 20 years of experience as a journalist. She spent five of them researching and writing her debut book, When Postpartum Packs a Punch: Fighting Back and Finding Joy. It’s available on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, IndieBound, Powell’s, and local libraries in the U.S., Canada, and New Zealand. Cowan lives in the Chicago area with her husband and two children. Online you can find her at www.kristinacowan.com.

When Postpartum Packs a Punch

By Kristina Cowan

Childbirth is a beautiful thing. It can also be terrifying and leave new parents traumatized.

In the Western World, it’s tricky to talk about trauma and the mark it leaves on us. It’s as if we believe whatever happens to the body doesn’t affect the mind. Quite the opposite is true, though. Trauma disturbs our mental health.

I learned that after the birth of my first child, Noah. My OB-GYN had encouraged me to induce labor ahead of my due date, painting it as the best-case scenario: I could organize childbirth on my terms, and fit it into my schedule.

But nothing went according to plan.

Shortly after I settled into my delivery room, a nurse told me on average, inductions lasted 24 hours and often resulted in C-Sections. Why hadn’t my OB mentioned this? Equipped with that information, I wouldn’t have induced. I trusted my doctor. She meant no harm by encouraging an induction. But it was as if my coach had advised me of our game strategy after I’d started playing. I felt misled; powerless.

My body reeled from the medicine used to spur labor. After I’d pushed unsuccessfully for three hours, my doctor and I agreed she’d use forceps to deliver the baby and avoid a C-section. It worked. But the forceps required a powerful drug cocktail that numbed my body and mind. As Noah was born, it seemed as if I were watching everything happen to someone else. I still mourn the loss of being fully alert when my first child was separated from me and pulled into the world.

The forceps injured me, and I needed a significant number of stitches. A day after I went home with my baby, I was in the emergency room. Wracked by pain worse than childbirth, I thought I would die and strand Noah. I was severely constipated and my bladder was distended, to more than twice its size. My body so swelled, I weighed more than I did while pregnant. Thanks to the ER doctors, my OB, an enema, and a catheter, I slowly crawled my way back to physical wellness.

My mind was another matter.

A week later, I started crying. The endless tears were often inexplicable. Images of the baby plummeting out the window or down the trash chute horrified me. I soon sought my doctor’s help and learned that I was battling postpartum depression (PPD).

Postpartum Depression: What I’ve Learned

I quickly sought treatment through medication and therapy, and the combination was effective. As I healed, I saw how the trauma of Noah’s birth had contributed to my postpartum depression. The journalist in me knew it was a story. I informally interviewed friends and family and discovered that postpartum depression isn’t uncommon. I widened my research and conducted formal interviews. Soon I had more than enough for an article. I could write a book.

So I did.

When Postpartum Packs a Punch: Fighting Back and Finding Joy, my first book, published in the spring of 2017. My story is the launch pad for the book, but the heart of it lies in stories from parents across the U.S. and the U.K., and their experiences with birth trauma and mood disorders.

Before I had PPD, I knew little of it. Writing the book was a five-year education. Some of the most important things I learned are:

– PPD strikes more often than we think. While the incidence varies, the typical range is between 12 and 25 percent of new mothers. In some high-risk groups, rates are as steep as 40 percent or more, according to Depression in New Mothers: Causes, Consequences and Treatment Alternatives. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists says during pregnancy, between 14 and 23 percent of women will battle symptoms of depression.

– Postpartum depression is a perinatal mood and anxiety disorder (PMAD), and it’s the one getting the most attention. But it’s not the only one to affect new parents. Others, like postpartum anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, and psychosis are equally harrowing.

– Most new parents don’t seek or receive adequate care for a mood disorder. They might mistake it as simply an adjustment to parenthood. Or they fear others will pass judgment—maybe even take their babies away—so they stay silent.

– Dads get PMADs, too. Research in the Journal of the American Medical Association shows that among U.S. men, the rate of paternal depression is 14 percent. But the topic doesn’t get much attention from researchers and clinicians, and it usually escapes public awareness.

Facing Trauma, and Getting Past It

The forceps my doctor used to help deliver Noah, my resulting injury, the feelings I had of being violated and misled—these are common characteristics of a traumatic birth. In my case, birth trauma was compounded by the trauma of losing my mom when I was 15. Memories of that loss, along with the pain of her absence when I became a mom myself, bubbled to the surface.

We can’t fully heal from trauma until we address it. I discovered that halfway through writing my book, so I reorganized it. I placed trauma at the center and examined therapies for healing, such as eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). EMDR uses bilateral stimulation, like a patient’s eye movements, to help target and process disturbing memories and feelings. CBT focuses on a patient’s distorted, unhealthy thoughts and modifies them and their resulting behaviors, thereby changing the person’s mood and emotions for the better.

As we learn more about trauma, we’ll discover how common it is. Ideally, that commonality should help us release our fears of admitting that at some point—even with the births of our beloved children—we endure trauma.

On behalf of IFWIP team, we wish Kristina and her family all the very best for the future.